History Wars

The Battle for Historical Authority

By James Hughes

This essay will focus on the “History Wars” of conflicting historical narratives, different approaches to studying history and ultimately, the battle for authority, particularly the conflict between popular history and academic history (Popkin, 2016, 154). In essence, a work of popular history is written for the purpose of reaching mass audiences while academic history is written for specialists. The historical construction of national identities is another crucial aspect of the “History Wars” as countries debate and have debated on historical themes such as nationalism and imperialism. The debate on how historians should construct the past will have repercussions for the future of historical studies because, “he who controls the past controls the future. He who controls the present controls the past” (Popkin, 2016, 113).

Even though the term “History Wars” was not coined until the late 20th century, the power struggle over which historical works will be promoted and accepted has a rich historiographic tradition (Popkin, 2016, 154). In 1439-1440, Lorenzo Valla’s Discourse on the Forgery of Constantine challenged the Catholic Church’s claim that the Roman Emperor Constantine gave the Catholic Church jurisdiction over Rome in the 4th century (Popkin, 2016, 48). Through his use of new language from the 15th century, Valla’s historical work challenged the Catholic Church’s authority. In 17th century France, King Louis XIV used propaganda history, such as Cardinal Bossuet’s Universal History, to defend “the absolute power” of the monarchy (Popkin, 2016, 57). In the 17th and 18th century, the Enlightenment historians challenged the Renaissance movement’s perspective on historical studies by emphasizing the progress of humanity instead of classical Roman and Greek works (Popkin, 2016, 61). After World War I, the “general faith in human progress that had underlain the development of academic history in the nineteenth century was shattered” and the struggle to define the past has continued to be a contested issue(Popkin, 2016, 106).

Ever since Leopold Von Ranke led the “professionalization” of history movement in the 19th century, academic history has attempted to provide a more accurate and factual account of the past (Popkin, 2016, 76). Ranke’s historiographic “revolution” inspired academic historians to be neutral within their works (Popkin, 2016, 76). Ranke advocated that historians use “primary sources” and new “scientific” methods to write historical narratives (Popkin, 2016, 75-76). By the time that popular history surged in popularity in the 1960s and 1970s, Ranke’s legacy had already made a long-lasting major impact on the history profession. Popular history, however, came into conflict with Ranke’s legacy because its first purpose was to reach mass audiences, not to be objective. Due to its perceived lack of objectivity, “popular history is often looked down upon by more academically minded historians” (Norton, 2013). The debate between popular and academic history initiated another power struggle for control of historical studies.

In the 1960s and 1970s, popular historians such as Pierra Nora, Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie and George Duby successfully marketed their works to mass audiences (Popkin, 2016, 154). George Duby wrote that one hundred years after works on history withdrew from the marketplace because they were written only for those who understood history, these works were revised to become more availabe to the mass audiences (Popkin, 2016, 154). Not only did academic historians attack popular history for its lack of objectivity, academic historians attacked popular history because its consumers and the general public, were fascinated with flashy topics. For example, British “university historians” attacked the general public’s interest in the “restoration of wealthy ‘stately homes’” because it placed too much importance on the lives of the rich and powerful (Popkin, 2016, 154). In this case, academic historians pushed for history that is more accessible and relatable for the common man.

.jpg

)

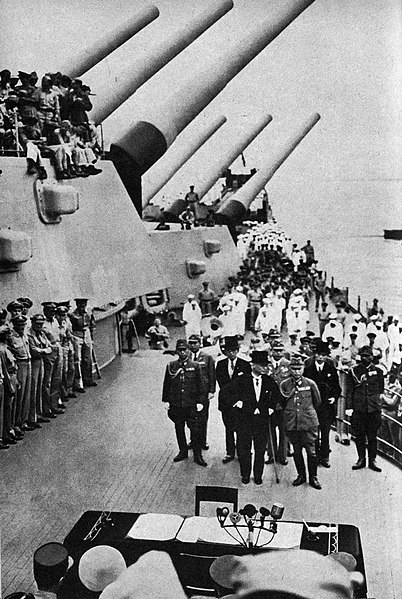

In 1994, the divide between popular and academic history was on full display in the United States when the Smithsonian attempted to bring the Enola Gay, the plane that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima during World War II, to its Washington D.C. museum (Linenthal, 1996). In alignment with the mainstream academic historical perspective, the Enola Gay exhibit was designed to show “the devastation and human suffering caused by its use” (Popkin, 2016, 160). The exhibit was seen by many Republicans and veteran groups as “anti-American” and “projecting the ‘countercultural values’ of the Vietnam era onto America’s last good war” (Linenthal, 1996, p. 2). But for academic historians like Beverley Southgate, who was not involved in the development of the Enola Gay exhibit, the agenda of all modern history should not be to promote nationalist histories but to advocate for “that international community to which now we all belong” (Southgate, 2005, 74). In this case, not only do the believers of popular history and academic history have different viewpoints but they have different values. The Enola Gay exhibit was later discarded by the museum in 1995. But, the idea of the exhibit itself struck at the heart of the “History Wars”, a term that drove Edward Linenthal to write the book “History Wars: The Enola Gay and Other Battles for the American Past” (Linenthal, 1996).

The historical battle over the Enola Gay is not only crucial from a historical standpoint of showing “what actually happened,” as Ranke stated, but it had a profound impact on how America saw its national identity (Popkin, 2016, 76). While certain examples of American popular history glorified America’s role in dropping the atomic bombs on Japan, such as its inclusion in President Truman’s Presidential Library, the consensus among academic historians is to take a more objective approach by analyzing the devastating impact the atomic bomb had on the Japanese people (The Harry S. Truman Library and Museum, 2018) (Linenthal, 1996, 131). If the historical consensus is that the United States unnecessarily dropped the atomic bombs, then the United States unjustifiably killed hundreds of thousands of civilians (Linenthal, 1996, 79). President Truman’s advisor, Admiral Leahy, estimated that an invasion into Japan would have resulted in the deaths of 50,000 American soldiers and other reports had estimated 500,000 dead American soldiers (Linenthal, 1996, 54-56). If the historical consensus is that the United States was justified in the dropping of the atomic bombs because it saved 50,000 or up to 500,000 American soldiers, then the United States was the heroic winner of World War II.

The atomic bombings on Japan is not the only controversial issue in the American History debate between popular and academic history. In the academic historian Anders Stephanson’s book, “Manifest Destiny: American Expansionism and the Empire of Right”, Stephanson takes a more critical viewpoint of the popular historical perspective that glorified America’s westward expansion (Stephanson, 1995). Native American historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, in her book “An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States”, aggressively attacked the United States, as an imperialist nation, for perpetuating a “genocide” against Indigenous peoples and displacing native tribes off their land (Dunbar-Ortiz, 2014). Dunbar-Ortiz advocated that the history of United States and Indigenous relations be studied through a settler-colonial approach. Differing views of how the United States has handled Indigenous relations have sparked a debate concerning how American’s view their past. Was the United States’ expansion westward justifiable? Has the United States committed genocide against Indigenous individuals? These questions are critical to the battle to define America’s past.

The rise of varying viewpoints on America’s past has led to a political debate on how history should be taught in educational settings. Particularly, American politicians have struggled with the issue of how critical the history curriculum should be of America’s past. While “the history wars in the United States often saw academic historians defending a pluralistic approach to the past” that promoted an inclusionary mindset for different social groups, conservative politicians often thought that academic historians were seeking to promote “politically correctness” (Popkin, 2016, 159). A “pluralistic approach” to history emphasized feminist history, non-western history and other important social histories (Popkin, 2016, 159). However, not all academic historians believe that a heavy emphasis on plurality is good for historical studies. Mark Lilla, a historian at Columbia University, attacked the growing trend of identity politics in history by stating that “the achievements of women’s rights movements, for instance, were real and important, but you cannot understand them if you do not first understand the founding fathers’ achievement in establishing a system of government based on the guarantee of rights” (Lilla, 2016). The battle for control of America’s past not only reaches across the distinctions between the popular and academic history but it’s impacted by the political debate of what should be included in history curriculums across the country.

Frequently, the lack of separation between popular history and myths has been criticized by historians. Even though popular history is sometimes criticized for a lack of objectivity and vigorous research, it provides a valuable benefit to society. An academic historian, David Lowenthal, expressed his support for popular history, specifically “Disneyland’s talking Abraham Lincoln”, by stating that “better a misinformed enjoyment of history than none, a lighthearted dalliance with the past than a wholesale rejection of it” (Popkin, 2016, 155). Lowenthal is correct in his assessment of popular history because it is beneficial for the history profession to have a greater audience. While Disneyland’s interpretation of Abraham Lincoln may not be the most critical or in-depth historical viewpoint, it gives the general public a broad understanding of one of America’s most important historical figures. Dangerous and aggressive national narratives, like the one promoted by Hitler’s Germany, should be quickly identified and combatted for the betterment of the world. However, the history profession should not lose potential consumers because an intellectual elite is upset that a “lighthearted” historical representation is not scholarly enough (Popkin, 2016, 155). In “What is History For?”, Southgate claims that all history has an agenda and it is unreasonable for a historian to be completely objective and to “consider all angles” (Southgate, 2005, 24 & 25). Since scholarly historians even admit to academic history’s shortcomings, are scholarly historians being unfair in their criticism of popular history?

The recent surge in social media has had a large impact on the study of history (Haydn, 2017). Historical facts can be acquired by the click of the button. Not only can history be studied through different mechanisms, the amount of people who can spread and share popular media has dramatically increased. When coupled with the postmodern movement of the late 20th century that challenged academia’s role in presenting history, these trends will have unforeseeable consequences on which authority will decide how history will be presented in the future (Foucault, 1989) (Popkin, 2016, 138). Will non-historians promote popular history through social media? In the aftermath of the 2016 Presidential election, the term “fake news” has been used to describe false news stories (Larderi, 2017). The issue of “fake news” has raised questions about the reliability of easily available information. Will social media be used to spread false historical narratives in a manner similar to “fake news” in politics?

At the heart of the “History Wars,” there is a conflict over who has the authority to spread historical works. The battle for control over the future of history is one of the most crucial topics for the history profession because it’s deeply intertwined with other key historical trends and themes (Popkin, 2016, 153). This struggle for the authority and power to tell history expands beyond just the distinctions between popular and academic history and which of those historical methods will become more commonly used by future historians. Will such subjects as Marxist history, objective history, feminist histories, nationalist history and historical sociology become more commonly used in academic curriculums? Will certain historical methods be taught with greater emphasis than others in history departments across the globe? Historians have to decide if they are going to compose their historical work for mass audiences with less of an emphasis on objectivity or if that work is to be constructed for scholarly purposes. The question of who has control and the authority to decide how to present history has academic, political, and social ramifications on how the public views the past and more importantly, which historical narratives will prevail in the future.

Sources:

Greenberg, Douglas. 1998. “`History Is a Luxury’: Mrs. Thatcher, Mr. Disney, and (Public) History.” Reviews in American History 26 (1): 294.

Gast, John. 1873. “American Progress.” Still image. Library of Congress. 1873. //www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppmsca.09855.

Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. 2014. An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. ReVisioning American History. Boston : Beacon Press, [2014].

Gage, Beverly. 2017. “An Intellectual Historian Argues His Case Against Identity Politics.” The New York Times, sec. Book Review. April 17, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/15/books/review/mark-lilla-the-once-and-future-liberal.html.

Popkin, Jeremy D. 2016. From Herodotus to H-Net : The Story of Historiography. New York ; Oxford : Oxford University Press, [2016].

Linenthal, Edward, and Tom Engelhardt, eds. 1996. History Wars : The Enola Gay and Other Battles for the American Past. 1st ed. New York: Metropolitan Books. https://eds.b.ebscohost.com/eds/detail/detail?vid=1&sid=a41a50f4-3d27-402e-ad4f-c4935fe977c6%40sessionmgr120&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmUmc2NvcGU9c2l0ZQ%3d%3d#AN=unm.34077658&db=cat05987a.

Guyver, Robert, and Tony Taylor. 2012. History Wars and the Classroom : Global Perspectives. Charlotte, North Carolina: Information Age Publishing. https://eds-a-ebscohost-com.libproxy.unm.edu/eds/detail/detail?nobk=y&vid=4&sid=025c5d45-cf04-40a7-9977-4ec800f8ab8f@sessionmgr4007&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmUmc2NvcGU9c2l0ZQ==#AN=469959&db=nlebk.

Hogeland, William. 2009. Inventing American History. Boston Review Bks. Cambridge : MIT Press, 2009. http://libproxy.unm.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat06111a&AN=unm.EBC3339015&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Stephanson, Anders. 1995. Manifest Destiny : American Expansionism and the Empire of Right. [A Critical Issue]. New York : Hill and Wang, 1995.

McNeill, William H. 1986. “Mythistory, or Truth, Myth, History, and Historians.” The American Historical Review 91 (1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.2307/1867232.

Munslow, Alun. 2007. Narrative and History. Theory and History. Basingstoke : Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

The Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. n.d. “Presidential Years: Decision to Drop the Bomb.” Presidential Library’s Website. Truman Library. Accessed April 18, 2018. https://www.trumanlibrary.org/hst/d.htm.

Strauss, Gerald. 1991. “The Dilemma of Popular History.” Past & Present, no. 132: 130–49.

Lowenthal, David. 1985. The Past Is a Foreign Country. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire] ; New York : Cambridge University Press, 1985.

Engels, Karen. 2017. “The Story of Us.” Educational Leadership 75 (3): 38–42.

Southgate, Beverley. 2005. What Is History For? 1st ed. London and New York: Routledge.

Casey, John. 2000. “Why, 60 Years on, Zeros Are Bombing Pearl Harbour Again; As Disney Recreates the Infamous Raid by the Japanese for a Film Dubbed ‘the New Titanic’, One Leading Academic Attacks Hollywood’s Treatment of History.” Mail on Sunday (London, England), 2000, Solo Syndication edition.

Norton, Elizabeth. 2013. “Writing Popular History: Comfortable, Unchallenging Nostalgia-Fodder?” College Source. History Matters. History Brought Alive by the University of Sheffield. August 28, 2013. www.historymatters.group.shef.ac.uk/popular-vs-academic-history/.

Lilla, Mark. 2016. “The End of Identity Liberalism.” The New York Times. Sunday Review: Opinion. April 18, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/20/opinion/sunday/the-end-of-identity-liberalism.html

Haydn, Terry. 2017. “The Impact of Social Media on History Education: A View from England.” Yesterday and Today, no. 17 (July): 23–37.

Foucault, Michel. 1989. The Archeology of Knowledge. London: Routledge.

| Malik, Kenan. 2018. “Fake News Has a Long History. Beware the State Being Keeper of ‘the Truth’ | Kenan Malik.” The Guardian. April 22, 2018. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/feb/11/fake-news-long-history-beware-state-involvement. |

Lardieri, Alexa. 2017. “Fake News, Real Impact.” US News & World Report. April 22, 2018. https://www.usnews.com/news/national-news/articles/2017-09-20/team-lewis-study-examines-how-fake-news-impacts-public.