Roman Historiography

By Louisa Schoeller

Roman historians, like Livy, and Tacitus were influenced by greek historians like Herodutus and Thucydides whom you read about in Greek Historiography. Their approaches to history would eventually ‘evolve’ into national histories, as a majority of their Roman historical works emphasized the Romans’ superiority in relation to the rest of the world. The inclusion of fables and myths would create new challenges as it would be harder to determine what is the ‘truth’ that they are setting out to find and what is the ‘fictional’ or unimportant details.

Roman historians faced a major challenge as they worked on their writings since most of Roman history was transmitted through oral traditions. These oral histories been passed down from generation to generation so it’s almost impossible to note what are the facts and what are the myths. Oral histories not only expressed the Roman historians limited number of written sources at their disposal but also the complication of having to determine what is fact and what is myth in a specific account.

Roman Historiography would have been something that remained limited to the upper classes of Roman society. During the time of the Roman Empire, only the elite would have had the access to upper levels of education and possessed the ability to read and write. Allowing the smallest percentage of the population the opportunity to focus their history on reflecting themselves and their ancestors while leaving out the majority of the population. The fact that historical writing remained a privilege of the upper class might allude to the propagandist tendencies and the nationalist approach that Roman historians have been characterized by. The ruling class would want to maintain their power and what better way to do that than by writing themselves into the history and development of the Roman Empire itself.

All of these aspects impacted Roman Historiography in their own ways, some reaching far beyond the time of the Romans. This essay will focus on Roman historiography in terms of national histories and religion, as both held importance in Roman history.

National Histories

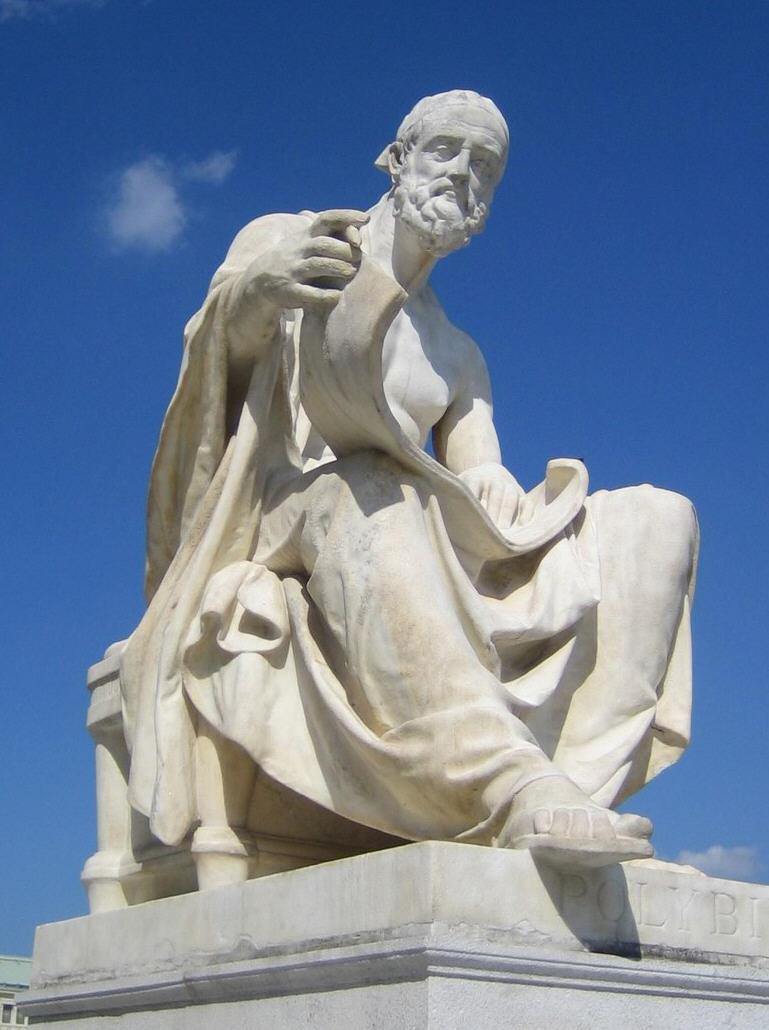

The Romans are well-known for their military expeditions that would expand their empire’s borders, wealth, and influence across the Mediterranean world. Polybius wrote several works that emphasized the Romans role in the world as they knew it. He would not use rhetoric due to the fear that it would inhibit him conveying the truth as he had set out to do (Sorek, 2012, 81). Polybius studied and wrote his histories with the aim of trying to understand what elements or values could explain Rome’s success. Were these motives economic,Political, Military,or possibly social? He focused specifically on Roman history and chose not to include outside societies and the lower classes in his works as they were considered “less noble” (Sorek, 2012, 80). Roman historians that followed Polybius, like Livy, Julius Caesar, and Ammianus Marcellnius, would officially create the genre of national histories. National histories can be defined as “the story of a single political community over an extended period of time” (Popkin, 2016, 32). In terms of the Romans, this would be the emphasis of the events of the past in relation to the Roman’s imperial success.

The goal of national histories was to place importance upon themselves above the rest of the world. The world the Romans lived in resembled their success as one of the most powerful empires in Antiquity; which they wanted to be conveyed through their histories. This would also include the histories of their families and what they had contributed to Rome’s success. “They were proud of their traditions - what had begun as family memories became over the centuries a collective national mystique” (Mellor, 2013, xvi). The Romans wanted to remain true to their past, in their present and by writing national histories where they kept their ancestors and their own actions alive.

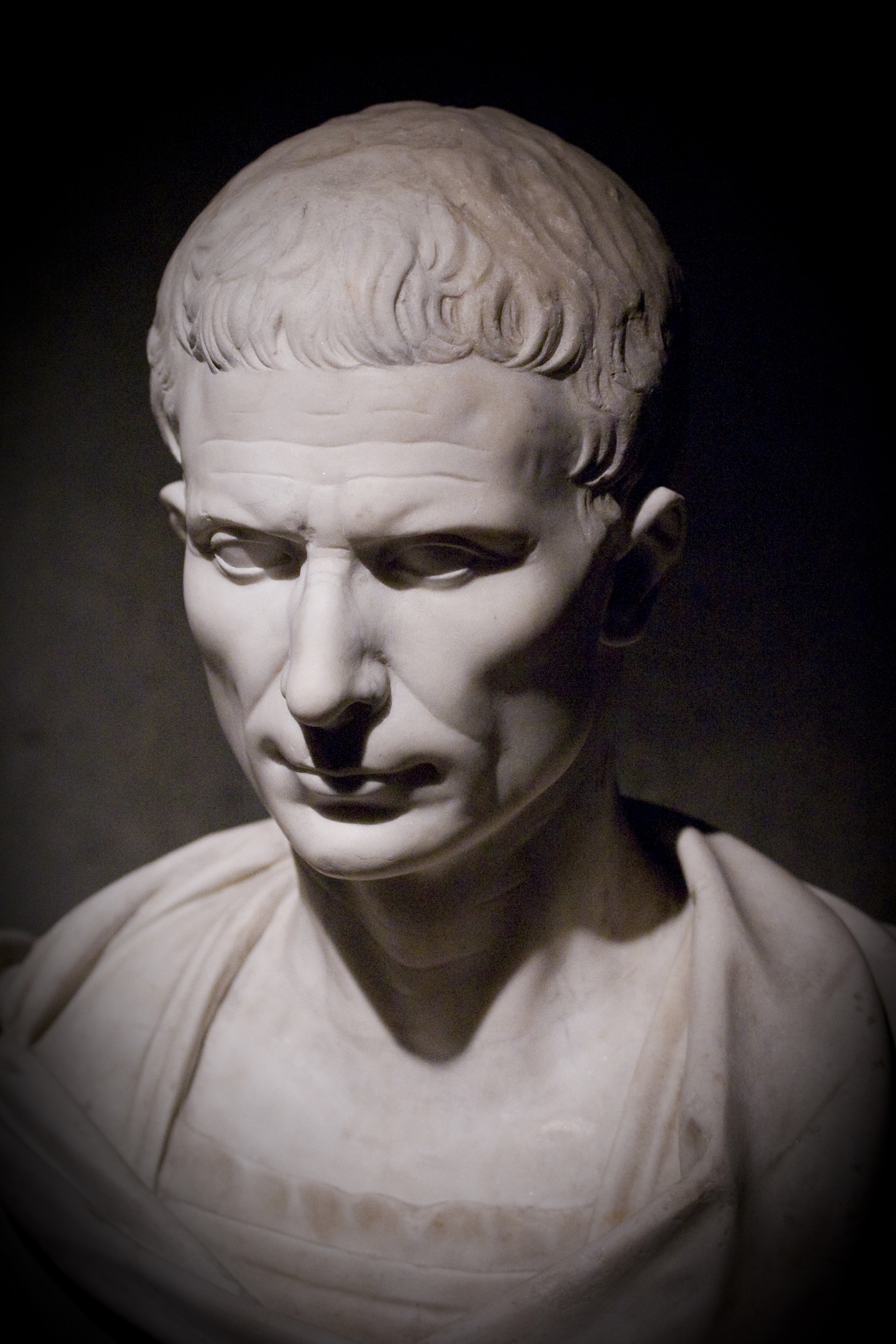

Julius Caesar was a historian who promoted propaganda, although, his works did follow in the tradition of a national history as he did promote the things he had already done and wanted to continue to do for Rome. He had come from an elite family in the Roman Empire that had gone back several generations; his dad and grandfather held public offices during their lives, just as Caesar had (Sorek, 2012, 91). He is known for his military successes than for his contribution to Roman Historiography. Two of his most notable works are the The Civil War, a memoir in which he describes in detail his conflict with Pompey the Great, and the Gallic Wars, a memoir that details his military campaigns in the Germanic lands across the Rhine (Sorek, 2012, 93). Susan Sorek, in Ancient Historians A Student Handbook, argues that both of these works were written as propaganda that not only emphasized Caesar himself but also the success of the empire. His version of Roman historiography had then, taken on a persuasive rhetoric that could be used on the lower classes of their society when Julius needed to round up support. He wanted to explain why his military expeditions were necessary and why the people should remain supportive of these causes. In order for him to have conquered the lands he had, he needed to have the support of Rome.

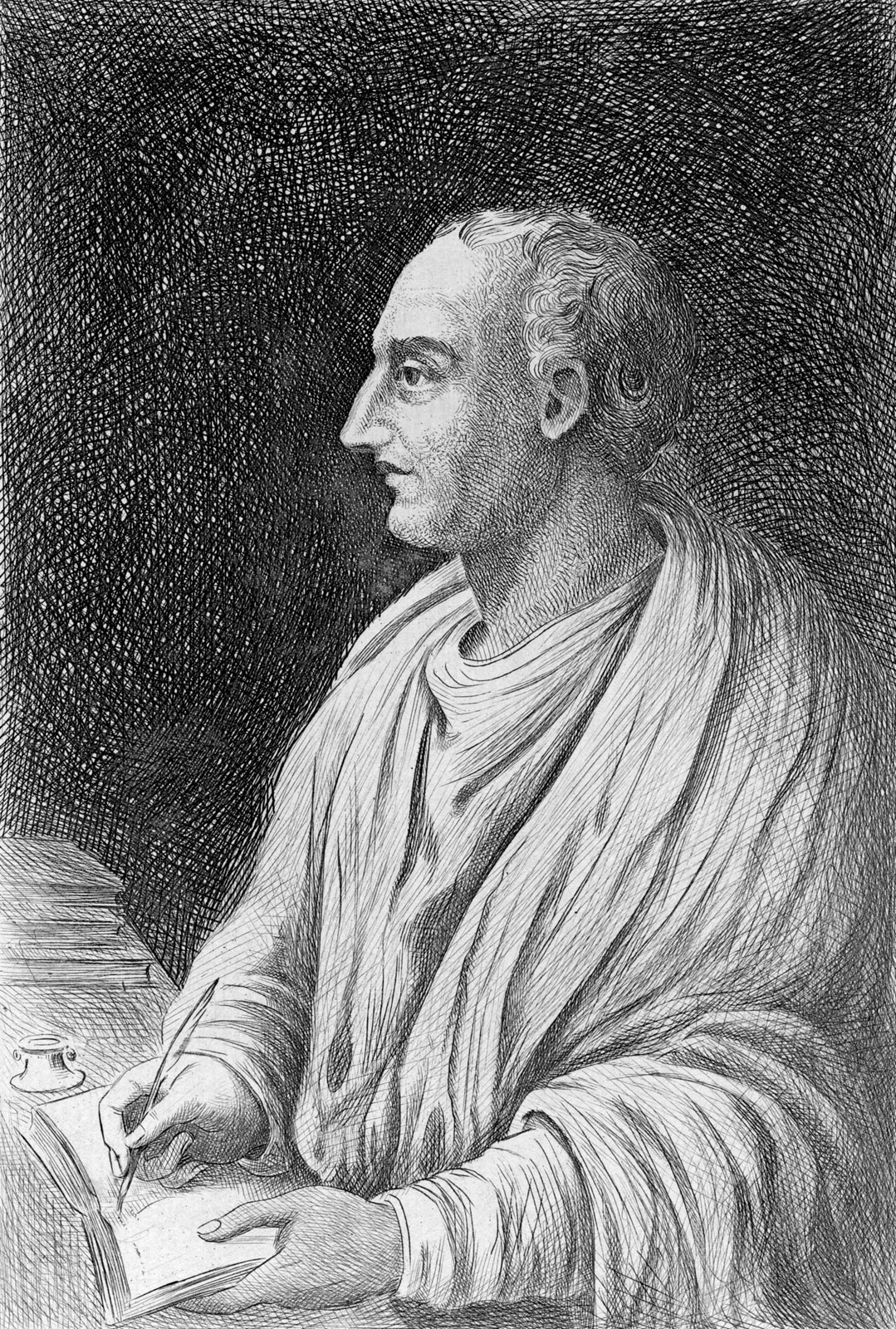

Livy did not have any military or political experience as Julius Caesar did, he came from an intellectual background and approached his writings by looking into “Roman history from a moral standpoint” (Sorek, 2012, 106). He attempted to understand the impact of morals or the impact of the lack of morals had on the success of the empire, as he does in his account of the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE), where he discusses the moral choice that one of the figures had to make: to stand with Rome or against Rome (Sorek, 2012, 106-107). While the Romans had ‘respected’ the Greeks and all of their cultural innovations (such as, written histories); the Romans worked to distinguish themselves from the Greeks. It’s almost as if the Romans ‘cherry-picked’ the aspects of Greek culture that they felt amplified Roman values and used them to their advantage. Livy would talk about other cultures that surrounded the Romans, such as the Carthaginians in his Second Punic War account as well, but only to make the distinction of the superiority of the Romans to those who are not Roman (Sorek, 2012, 108-109). Again, it appears that the approach of national histories allowed Livy to distinguish the Romans from those surrounding them. Could this be considered propaganda? Sure, it can, as it paints the Romans in a superior manner, whether or not the Romans were actually superior to those around them. However, it can be argued that the use of national histories was the Roman’s version of propaganda since the histories written by some historians seemed to have only been written with trying to promote a cause/war like Julius Caesar.

Both Livy and Julius Caesar take on this national history form in order to convey the greatness of the empire. No matter if the historian focused on the military history or the complete history of the empire, both Livy and Julius Caesar take on a superior tone in their writings that emphasize the Romans in a brighter light when compared to other races or civilization at the time.

Roman Religion, Christianity, and Historiography

Early Roman civilization is known to be a polytheistic society, a society that believes in more than one God. Their deities include Jupiter (better known as Zeus in Greek Mythology), Venus (Aphrodite), and Mars (Ares). The Romans believed that every aspect of their lives, their actions, and their successes were dependent upon the happiness of their gods. They believed that the gods and goddesses played a significant role in the course of their lives and the success of the empire. Their religious beliefs and superstitions would have carried over into their political and military lives/decisions, so why would their religion not impact their history? Roman religion believed in and placed value on the idea of omens or hints from the heavens when trying to make any big decisions as they were seen a guidance from the deities above. Considering how important and central their religion was to the Romans, it can be surprising that it is not one of the focused upon or emphasized themes in their historical writings.

Ammianus Marcellinus was a Roman historian who worked to maintain the traditional practice of Roman religion in a Christian influenced society. Christianity was legalized by Constantine in 313 CE. While it is unclear in his work on the true feelings he felt towards Christians and Christianity, as he never completely goes into a discussion surrounding their religion. In his work, Res Gestae, he explores a Roman world that had come into contact with a different religion. As he remained true to his religious traditions, he also stayed true to Roman historiographical traditions, which meant not placing an importance on the societies, people, and ideas that fall outside of the Roman sense of the topic (Hunt, 1985, 193). Christians were not a primary focus of his writing, nor did he want them to be but living under Christian emperors, a subject of discussion for him. Ammianus might not have had a problem with Christianity itself, but rather its intrusive nature in the political realm of the empire (Hunt, 1985).

The clash between the two different religions towards the end of the empire illuminates the Romans emphasis on their own traditions and themselves. “Among the exceptions was that cruel one which forbade Christian masters of rhetoric and grammar to teach unless they came over to the worship of the heathen gods” (Mellor, 571). If one wanted to be a Roman, one had to believe in the various deities in Roman religion; not in a single God. By leaving Christians out of his writings, he left them out of his version of Roman history. Ammianus remained devoted to emphasizing the greatness of Rome, even though the empire had begun to crumble during his life. Ammianus Marcellinus is one of the few Roman historians who touched on religion in his writings. He never gave Christians predominant presence in his writings as they were not meant to be his focus; Rome was his focus.

Conclusion

Roman Historiography had been influenced by the writings and styles of Herodotus and Thucydides but had developed in its own way. The emphasis on the empire and its success is apparent through multiple Roman historians’ writings and something that was characteristically Roman at this time. They wrote about the world in the way they understood it: with them being at the center.

The creation of the national history genre allowed them to write their history with a complete focus on the Empire, its success, and those who brought about that success (the elite class/families). Polybius’s, Livy’s, and Julius Caesar’s works all highlight the emphasis on the superiority of the Romans, although, they are all done in very different ways. Ammianus Marcellius’s writings also fit into this model as he stuck to the national history form but included limited discussions on the Roman and Christian religions.Roman historiography will extend into future generations of historical writing as Roman historians provided new models, new focuses on historical material, and new genres, that will be used throughout time. We can even see now that this genre of historical writing extends well past the life of the Romans, as other historic figures will use their national histories with the same goal of promoting propaganda.

Bibliography

Hunt, E.D. “Christians and Christianity in Ammianus Marcellinus”. The Classical Quarterly, Vol. 35, No. 1 (1985): 186-200. http://jstor.org/stable/638815.

Mellor, Ronald. The Historians of Ancient Rome An Anthology of the Major Writings. US; Canada: Taylor and Francis Group, 2013.

Popkins, Jeremy D. From Herodotus to H-Net: The Story of Historiography. New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Sorek, Susan. Ancient Historians A Student Handbook. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2012.